- Published:

- 18 January 2024

- Author:

- Professor Angharad Davies

- Read time:

- 4 Mins

We are 18 months on from the launch of NHS England’s Women’s Health Strategy and Welsh Government’s Quality Statement for Women and Girl’s Health; 2.5 years have elapsed since the Scottish Women’s Health Plan was published. Voices in Northern Ireland are calling for a similar initiative.

These moves are welcome and there is much work yet to do. The 2021 ‘Women’s Health – let’s talk about it’ consultation, which preceded the publication of the NHSE Health Strategy, had almost 100,000 respondents; of these, 84% reported the perception that women’s healthcare experiences and concerns were not listened to.

Although women have longer life expectancies than men, they can expect to experience a greater proportion of their lives in ill-health; yet, they are under-represented in clinical trials and research. As a result, the strategy document not only reports that is there inadequate understanding of specific women’s health issues, but there is also a lack of appreciation and knowledge of the different manifestations of many conditions in women, compared with men.

In the latest Bulletin, we explore 3 examples of women's health issues relevant to pathology specialties.

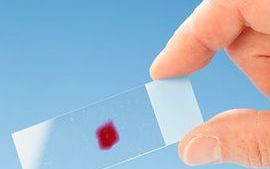

Sue Pavord, Consultant Haematologist at Oxford University Hospitals, writes about the ‘silent debilitator’ of iron deficiency. In her article, she focuses on its effects in pregnancy as well as its wider societal impacts, which can include impaired cognitive development, decreased work productivity and effects on immune function. Iron deficiency is a risk factor for postpartum haemorrhage and low haemoglobins are associated with higher maternal mortality, postnatal depression and poorer mother–child interactions. Recommendations for treatment and prevention are outlined.

The UK Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) team reports on transfusion risks in maternity, highlighting recurrent themes that have been identified as risks and how these can be minimised. Maternity units are particularly high-risk settings for transfusion; for example, 25–34% of all wrong blood in tube near-miss incidents reported between 2019 and 2022 involved blood samples taken by midwives. Other risks to mothers include anti-D immunoglobulin errors, avoidable transfusions with the attendant risk to future pregnancies resulting from red cell antibodies, and delays in the provision of blood components in emergencies such as major haemorrhage.

The importance of the annual SHOT reports is very clearly evident and the SHOT team emphasises the importance of learning from incidents, and involving and educating patients in their own care, with collaborative decision-making.

Perhaps a less immediately obvious gender disparity is access to and outcomes from organ transplantation. Lorna Marson, Professor of Transplant Surgery at the University of Edinburgh, provides a thought-provoking discussion on this, focusing on kidney transplantation, which is the most commonly transplanted organ.

Analysis by the European Committee on Organ Transplantation of the Council of Europe found that women are less likely to receive a transplanted organ; most studies have shown that women are less likely to be listed for transplant than men, with the disparity growing with increasing age. More recent UK data suggests that, while this situation may have improved, disparities relating to race, age and socioeconomic status persist, highlighting the challenges of intersectional health inequalities. There is much food for thought here.

Our 3 feature articles have caused me, for one, to reflect on how we can more successfully identify disparities, risks and obstacles to women’s health. As ever, we can only really do so when we cast assumptions aside and undertake reliable data collection and careful analysis – so we are very fortunate to have, in all our contributors above, dedicated clinicians who are doing exactly this.

Return to January 2024 Bulletin homepage