The Specialist Integrated Haematological Diagnostic Service (SIHMDS) concept was conceived in the 1990s and formally defined in the 2003 NICE Improving Outcomes Guidance (NG47), with the most recent update in 2016.1

Alongside huge advances in blood cancer treatment, there was a realisation that ‘improving the consistency and accuracy of diagnosis is probably the single most important aspect of improving outcomes in haematological cancer’.2,3

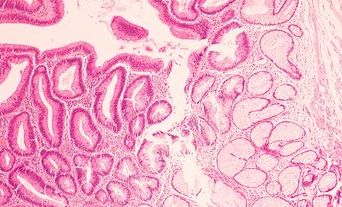

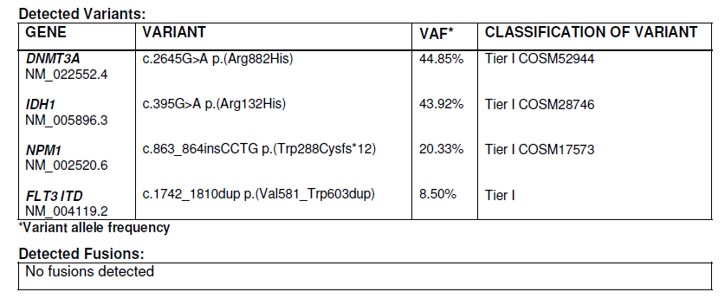

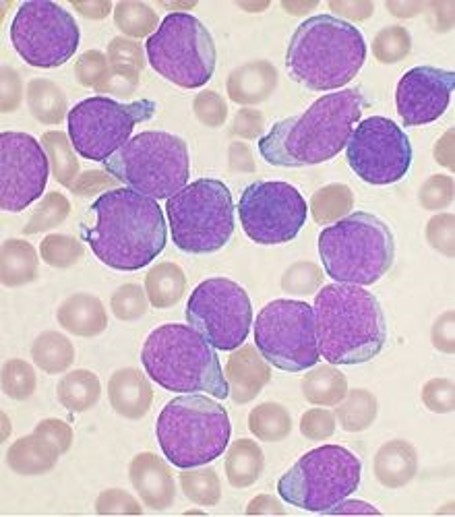

Accurate diagnosis of haematological malignancies involves integration of several diagnostic modalities with clinical information: haematological and histopathological cytomorphology, immunophenotyping by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, and molecular genetics, including next generation sequencing (NGS). This approach is built into the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of haematopoietic neoplasms. The key concept is integration; no single modality answers the diagnostic question.

An established SIHMDS laboratory has a single specimen reception and co-located laboratories at a single site. Multiprofessional staff work within a single quality management system, using predefined diagnostic pathways to analyse specimens using a variety of diagnostic modalities, then validate and correlate the results using a single IT system to produce an integrated diagnostic report. This model for blood cancers has also informed integrated reporting in solid tumours.4

The diagnostic challenge: evidence of harm

Evidence demonstrates the potential for patient harm if the SIHMDS model is not used. Early studies focusing on lymphoma suggested that 5–15% of haematological malignancies were being misdiagnosed outside an SIHMDS setting.4 This has major clinical consequences: cancers missed, benign conditions treated as cancer, or the wrong kind of blood cancer diagnosed and treated. A relatively small investment in pathology at the beginning of the pathway has a far greater effect on the patient and on the NHS than high-cost drugs.

The challenge posed by the NICE guidance in 2003 demanded that this diagnostic inaccuracy be addressed urgently. Two decades ago, there was widespread heterogeneity of services and slow progress on establishing fully integrated SIHMDS labs that followed explicit standards. This was partly due to the need for investment in expert staff, advanced technology and quality systems, but also due to education and cultural changes.

Important insights into epidemiology came from SIHMDS pioneer networks like the Haematological Malignancy Research Network in Leeds.5 The National Cancer Peer Review Programme helped support the development of SIHMDS laboratories within cancer networks by assessing laboratories against NG47. As more SIHMDS labs became established, the sense of urgency abated with a general feeling that progress had been made. However, many issues remain, and we still have no definitive national picture on how many established SIHMDS are in operation and their coverage, although some organisations are looking at this.

Genomics: opportunities and challenges

There has been recent commissioning of the Genomic Laboratory Hub (GLH) networks to embed advanced genomic technologies in mainstream care.6 The GLHs have been tasked with a focus on just the genomic testing elements of SIHMDS labs but have not been asked to consider the other modalities. In theory, this should support increasing the genomic testing capability of SIHMDS labs but, in many regions, GLHs have led to a tension with the fundamental tenets of NICE guidance and integrated diagnostics.

The first recommendation of the NICE guidance is the gold standard to achieve an integrated diagnosis: all SIHMDS testing modalities should be co-located on a single site. This permits consolidation of expert diagnostic staff and expensive technologies and is more likely to result in reduced turnaround times, improved diagnostic accuracy and greater cost efficiency. SIHMDS laboratories have often been trailblazers by introducing NGS techniques into standard care, but not all SIHMDS have been able to lever the investment in staff and equipment needed for NGS. Some SIHMDS labs have had to make a pragmatic compromise, by sending some tests to other labs, adopting a networked model.7

The SIHMDS has an important role in helping patients access WGS and the return of results, via genomic MDTs. There is a lot of work needed to overcome scepticism to focus on patient recruitment, consent, results interpretation and turnaround times.

The NICE guidance highlights that these networked models are inherently less efficient than single site models: challenging integration, turnaround times, reflex testing and increasing costs. The GLH model has encouraged the consolidation of NGS into genomic hubs, which has enabled some networked SIHMDS laboratories without prior NGS Integrated diagnostics involves multiprofessional staff bringing together morphological, immunophenotypic and genomic analyses capability to access important panel testing. This model relies heavily on integrated IT systems that allow for seamless transfer of results or data, something that is rarely available in the NHS currently. Thus, those networked SIHMDS labs have to work harder to produce integrated reports and feed into multidisciplinary teams (MDTs). An SIHMDS will always need staff with expert genomic knowledge as it is inherent to integration and genomic MDTs.

The GLH model has been a challenge for wellestablished SIHMDS laboratories that have made historical investments in NGS technology, IT and staff expertise to ensure all SIHMDS modalities are available in one integrated laboratory. For an SIHMDS with established NGS panel testing, the clinical benefits of sending samples to a genomic hub is less clear, as it is inherently inefficient, reduces integration and is antithetical to the gold standard described in NICE guidance. There has been concern from SIHMDS services across England about the GLH model and the risks it poses to disrupting established SIHMDS labs. NICE guidance is based on peer-reviewed evidence and failure to follow it has medicolegal implications.

NHS-provided whole genome sequencing (WGS) is now being implemented at scale, with acute leukaemia being one of the current indications. The aim of WGS is to ensure patients have comprehensive genomic profiling alongside standard of care diagnostics to potentially access novel therapies, clinical trials and contribute to research.6

The SIHMDS has an important role in helping patients access WGS and the return of results, via genomic MDTs. There is a lot of work needed to overcome scepticism to focus on patient recruitment, consent, results interpretation and turnaround times. WGS will no doubt find its place and bring benefits for many patients, but the results will need to be integrated with other SIHMDS modalities as the other genomics techniques have done. In general, the SIHMDS model should create opportunities to strengthen relationships with tissue banks and academics and to help answer basic research questions.

People and pathways: inside and outside the SIHMDS

The relationship between pathology and clinical users is fundamental to all high-quality diagnostics. An SIHMDS has daily interactions with users to ensure samples get to the lab promptly and that advice on results is readily available. Those relationships are harder to sustain as laboratories get larger. A certain scale is needed to ensure that SIHMDS multiprofessional expertise and techniques are co-located and resilient, but that should not be at the cost of local relationships with users and participation in MDTs.

Leukaemias are often diagnosed after several years of abnormalities in a blood count that is flagged up by their GP.

There are also workforce challenges involved in training the haematopathologists of the future. An SIHMDS involves healthcare scientists and medical staff working and learning from each other, blurring the boundaries between professions and disciplines, but training pathways and curricula need to reflect this. Workforce is one of the biggest challenges facing the NHS.8

An SIHMDS needs to consider the population it serves and how patients access the SIHMDS. Inconveniently, patients with blood cancer rarely present with classic symptoms in a specialist haematooncology clinic, via two-week-wait pathways.

Leukaemias are often diagnosed after several years of abnormalities in a blood count that is flagged up by their GP. Many patients with leukaemia or myeloma present as an emergency. The ‘backdoor’ lymphoma is well recognised; lymphoid neoplasms are often found incidentally in tonsils, lymph nodes or skin biopsies and it is often helpful for haematopathologists to be down the corridor from colleagues in other pathology disciplines.

High-quality SIHMDS labs provide the most advanced diagnostics available, but pathways to access an SIHMDS can often be fragmented, with some tests from one region sent to more than one SIHMDS. Are all eligible patients equitably and consistently accessing an SIHMDS? There are many anecdotes that SIHMDS laboratories are not being used consistently, but little evidence of the extent of this issue. We need a systematic evaluation of progress on both NICE compliance and access.

Biology is messy

Advances in technology have enabled subdivision of blood cancers into increasing numbers of diagnostic and prognostic categories, with advances in therapy making these categories increasingly relevant to stratified medicine. The WHO classification is the haematopathologist’s bible. However, like the Bible in its early years, the WHO book undergoes regular revision, with now more than 200 disease entities. There was a hope that genomics would provide simple answers and trump other modalities, but the truth is that no single test provides an answer. Integration is the key and simple answers to complex questions rarely exist.

As we employ sophisticated and sensitive technology, we are increasingly identifying incidental somatic and germline variants.

Many cancers are preceded by precursor conditions such as monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis and clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential. As we employ sophisticated and sensitive technology, we are increasingly identifying incidental somatic and germline variants. Blood cancers are also moving targets; minor subclones present at diagnosis may be the source of relapsed disease. An SIHMDS also helps define remission status and measurable residual disease assessment is becoming increasingly important.

Summary

Much has been achieved over the past decades. In some ways, we appear to be living in the future, with advanced techniques now available for routine care. We still have a responsibility to ensure that the future is distributed equitably, that we ensure that all SIHMDS laboratories are high quality and that we can assure ourselves that all patients have consistent access to the most advanced diagnostics in the world.