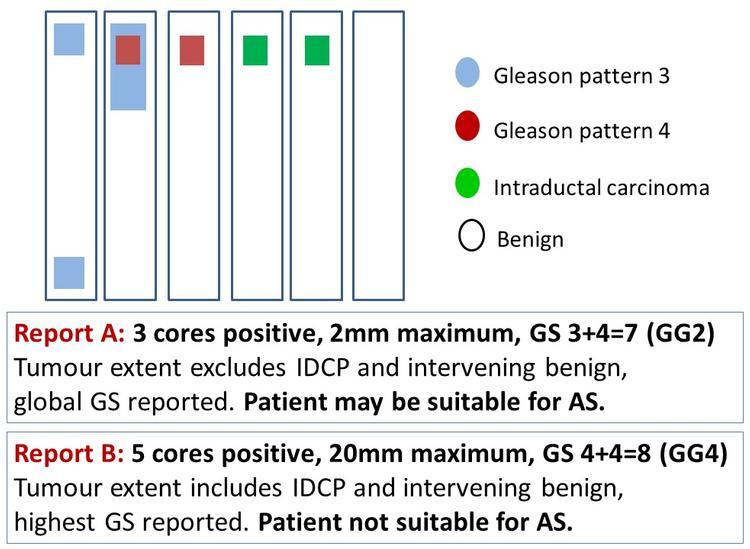

Prostate biopsies form a significant part of histopathology laboratory workload and pose unique processing and reporting challenges. Inter-observer variation in biopsies is inevitable in morphological continuums with inherent grey zones. Prostate biopsy reporting is, however, beset by avoidable variation, resulting from the use of different reporting rules. Unlike other biopsies, several indicators of tumour extent and multiple Gleason scores (GS) are commonly reported in prostate biopsies. This can result in a set of prostate biopsies being reported very differently by different experts with potentially serious consequences for patient management (Figure 1).

Recent publications from expert uropathology groups have exacerbated this problem with complicated, confusing and sometimes conflicting recommendations.1–3 It is important to recognise that most prostate biopsies are reported by non-expert practising pathologists who struggle to keep abreast of all the changes in the multiple subspecialties they report.

Unlike other biopsies, several indicators of tumour extent and multiple Gleason scores ... are commonly reported in prostate biopsies. This can result in a set of prostate biopsies being reported very differently by different experts with potentially serious consequences for patient management...

Histopathology guidelines generally advocate a one-size-fits-all protocol with identical data collected from each case. This standardised approach is, however, the antithesis of personalised medicine and may not represent optimal use of scarce resources.4

We highlight some significant issues associated with prostate biopsy reporting and briefly outline a simpler, more pragmatic, personalised approach to reporting prostate biopsies. This focuses on the clinical utility and effective communication of histopathology data items. The reader is referred to a recent genitourinary pathology symposium in which this approach is discussed in greater detail.5

Prostate biopsy reporting issues

Typically, prostate biopsy reporting focuses on the complete, precise and reproducible collection of data items. Each pathologist generally adopts a standard protocol, although this may vary among pathologists. Some pathologists would always include intervening benign tissue when reporting the extent of a discontinuous tumour, while others would always exclude this component. We explain why both these approaches may be inappropriate and why precision is neither possible nor necessary if the findings are appropriately communicated by pathologists and correctly interpreted by clinicians.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of prostate cancer is generally critical, so immunohistochemistry is commonly performed on small suspect foci. However, the diagnosis of prostate cancer in a needle core may be of diagnostic or prognostic significance. If there is definite prostate cancer in another core, then establishing the diagnosis of Gleason pattern 3 cancer in a small suspect focus would only determine the number of positive cores. In this scenario, it would be reasonable to render a diagnosis based on the balance of probabilities or to simply report the focus as suspicious without resorting to immunohistochemistry.

Some departments routinely double report prostate cancers, especially if they are limited in extent. However, the utility of such double-reporting or routine review of obvious cancers has been questioned.6 It is also important to consider the clinical scenario. Diagnosis of low volume, low-grade cancer has little clinical significance in a patient on an active surveillance protocol for histologically confirmed prostate cancer.

Tumour extent

Prostate cancer size cannot be reliably determined preoperatively so tumour extent in prostate biopsies reported as number of positive cores and extent of individual core involvement is commonly used to guide patient management.7 This information is however less important in digital and targeted biopsies. The former is performed for clinically advanced disease and, in the latter scenario, radiological size would be more accurate. Paradoxically, tumour extent in such specimens may be more relevant if biopsies show only a limited amount of tumour, as this may then be an incidental finding. In this setting, the clinical/radiological abnormality may be related to other pathologies, such as granulomatous prostatitis or urothelial carcinoma.

Prostate cancer size cannot be reliably determined preoperatively so tumour extent in prostate biopsies reported as number of positive cores and extent of individual core involvement is commonly used to guide patient management.

If multiple targeted biopsies are taken from a radiologically identified lesion, the number of positive cores would reflect the biopsy protocol rather than tumour extent. It would therefore be more appropriate to report the number of sites (rather than cores) positive in this scenario.

Tumour extent in individual cores provide only a rough estimate of the tumour size, owing to biopsy sampling error. Precise measurements are not necessary; these should be rounded up to the nearest millimetre or 10%. Millimetre core extent can be simply estimated by comparing tumour length to the field diameter. Percentage core involvement has questionable scientific basis as a 4 mm tumour in a 5 mm core (80%) is not indicative of a larger tumour than a 10 mm focus in a 20 mm core (50%). This has been recommended only because percentage involvement is easier to determine than tumour lengths, which can be difficult to ascertain when tumour is present in multiple cores within a single block. Eyeball estimation of percentage core involvement is sufficient.

Discontinuous tumour in a core may represent a single tumour weaving in and out of the biopsy plane or separate tumours. Discontinuous has been defined as at least 2 mm separation between the foci, but this cut-off was proposed mainly for convenience as it represents the diameter of a 10x microscopic field.8

We recommend considering tumour morphology when determining linear tumour extent in discontinuously involved cores. Larger separations could be considered continuous if tumour foci are morphologically identical. If the pathologist’s opinion is that the discontinuous foci in the most involved core may represent a multifocal tumour, then this possibility must be communicated with a short comment such as ‘15 mm (discontinuous) with maximum continuous tumour length of 6 mm in the set of prostate biopsies’. It is not necessary to report continuous tumour lengths in every core with discontinuous tumours.

Tumour grade

Biopsy GS often forms the basis of prostate cancer management, so pathologists strive to record a precise grade. The latter is often difficult in a morphological continuum with arbitrary cut-offs, so inter-observer variation is inevitable. Effective communication may be more important than precise grading. A pragmatic approach to Gleason grading has been previously described.9

Tumour grade is also a biological continuum with arbitrary cut-offs. A tumour at the lower end of the GS 7 spectrum and another at the upper end of the GS 6 spectrum would not be clinically different and hence could be managed as either GS 6 or GS 7. However, a tumour at the upper end of the GS 7 spectrum would be biologically different from a GS 6 tumour. Thus, it is not critical to precisely grade tumours at the borderline between patterns 3 and 4, provided the clinician is informed where a particular tumour lies within the risk spectrum. As clinicians do not usually view histological material, pathologists must effectively communicate the borderline nature of an individual case. Reporting of percentage pattern 4 can facilitate this communication in GS 7 tumours. Short comments such as ‘GS 6, focally bordering on pattern 4’ could also be helpful.

Prostate biopsies sample only a tiny fraction of the gland, so the biopsy GS provides only a rough estimate of the true tumour grade. In over 20% of patients with biopsy GS 4+4=8 (grade group 4), the prostatectomy grade was primary pattern 3 [GS 3+4=7 (grade group 2) or less].10

Biopsy GS is a morphological and biological continuum with arbitrary cut-offs and subject to significant sampling error. Reviewing pathologists should therefore refrain from modifying the reported GS in truly borderline cases.11 Rather than seeking to assign a GS to the case, they should assess whether the reported GS is acceptable. An explanatory comment indicating the borderline nature of the case would be more appropriate than a reassigned GS.

Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate

A major controversy relates to grading of invasive prostate cancer associated with an intraductal component (invasive-IDCP), with conflicting recommendations from two expert groups.1,2 The International Society of Urological Pathologists (ISUP) recommends incorporating the intraductal component into the GS, while the Genitourinary Pathology Society (GUPS) recommends reporting its presence separately from the GS. The merits of these recommendations are detailed in a head-to-head debate and a recent review paper.12,13

The rationale for excluding the IDCP component from the GS is that a small subset of IDCP associated with invasive carcinoma in prostate biopsies may represent precursor type IDCP. The latter would have a better prognosis than invasive-IDCP so incorporating IDCP into the GS could result in over-grading.

... perfection is neither attainable nor necessary when reporting prostate biopsies. A pragmatic approach focusing on clinical utility and communication of pathology data would ensure optimal utilisation of resources and better healthcare.

Both groups agree that IDCP is an adverse prognostic factor that precludes active surveillance and there is no evidence that the prognostic significance of invasive-IDCP is different from that of the corresponding Gleason pattern. Moreover, IDCP cannot be definitively distinguished from invasive prostate cancer by morphology or immunohistochemistry. The basal layer is often fragmented in IDCP, so absence of basal cells does not exclude the possibility of IDCP in which the basal cells are not represented in the examined plane of section.

A pragmatic approach would be to convey the adverse prognostic significance of invasive-IDCP by incorporating it into the GS and adding an explanatory comment in the rare scenario of a biopsy showing Gleason pattern 3 invasive carcinoma and an intraductal component.

Communication is key

As outlined above, it is critical that pathologists effectively communicate the message in histopathology reports. However, communication should not end with report authorisation. The pathologist’s role in multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings is to help clinicians interpret histopathology reports. For example, percentage pattern 4 is an important prognostic indicator in needle biopsies with GS 7 prostate cancer.

However, it is the duty of the MDT pathologist to explain that 80% pattern 4 (primary pattern 4, grade group 3) in a 2 mm tumour focus is not necessarily indicative of aggressive behaviour.

In summary, we explain why perfection is neither attainable nor necessary when reporting prostate biopsies. A pragmatic approach focusing on clinical utility and communication of pathology data would ensure optimal utilisation of resources and better healthcare.