The global status of polio

Poliomyelitis is caused by one of the three serotypes of the poliomyelitis virus (WPV1-3). A minority of infected people may get acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). The virus is spread via the fecal–oral route, mainly by contaminated water supplies. There are injectable inactivated and live oral polio vaccines (IPV and OPV), which have been available since the early 1950s. All vaccines are administered at least three times, to protect against all three viral serotypes.

The global control of poliomyelitis became a possibility due to universal vaccination, surveillance, national commitment and improvement in civic amenities. The vaccine generates lifelong immunity, which stops the proliferation of the virus in the intestines and thus breaking the chain of transmission. By the mid-1980s, large-scale polio immunisation had succeeded in many industrialised countries.1 That encouraged global efforts to eradicate the virus, so that it might not trickle back from affected areas to cleared zones. The ultimate aim is a polio-free world.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there was a global decline of 99% of wild poliovirus (WPV) cases between 1988 and 2017 – these have dropped from an estimated 350,000 cases across more than 125 endemic countries to just 22 reported cases. Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria remain the only three countries with ongoing cases. WPV-2 was eradicated in 1999 and no case of WPV-3 has been found since the last reported case in November 2012 in Nigeria.2 However, their circulation somewhere in the world might not be entirely ruled out. The WHO has planned to eradicate the poliovirus by the end of 2018. Its target is a complete certification process for all six WHO regions, which may lead to the global certification of polio eradication and preparation for eventual containment of all Sabin polioviruses at the time of OPV withdrawal.3

Progress with polio vaccination in Pakistan

Polio eradication activities started in Pakistan in 1994. Progress was made by achieving more than 95% coverage in supplementary immunisation activities, which was previously just 30% in large areas of the country. However, there still remained pockets of low coverage, which contributed to ongoing WPV circulation. There was a progressive decline in new polio cases from an estimated 20,000–30,000 cases per year only a few decades ago to just 40 cases in 2006. This was accompanied by genetic and geographic restriction of WPV circulation.4 However, Pakistan’s efforts against polio were neutralised by the progressively grave deterioration of law and order in certain areas of the country – mainly the areas bordering Afghanistan (see Figure 1 for map).5

Figure 1: Map of Pakistan showing regions and surrounding countries

The country faced a problem of militancy, with the militants and their families representing an unpredictably mobile population. Once displaced, they might carry the virus to other disturbed areas of the world, where they went to join the fighting. For example, China had been free from poliovirus since 1994. However, in 2011, in the troubled Xinjiang Province close to the border with Pakistan, the virus reappeared and there were seven confirmed paralytic polio cases in that region. The causative strain was WPV1 – genetically similar to that circulating in Pakistan.6 Similarly, during the conflict in Syria, many militants poured in from abroad, carrying poliovirus with them, to a country where its last indigenous case had occurred in 1999. That outbreak had physically crippled at least 13 children by October 2013. Genetically, the causative viral strain had come from Pakistan. Subsequently, the same virus circulated in the Middle East and North Africa. Molecular testing and genetic sequencing of the strains of poliovirus isolated in the sewage of Egypt, Israel and Palestine in 2012 had an established link to such strains.7

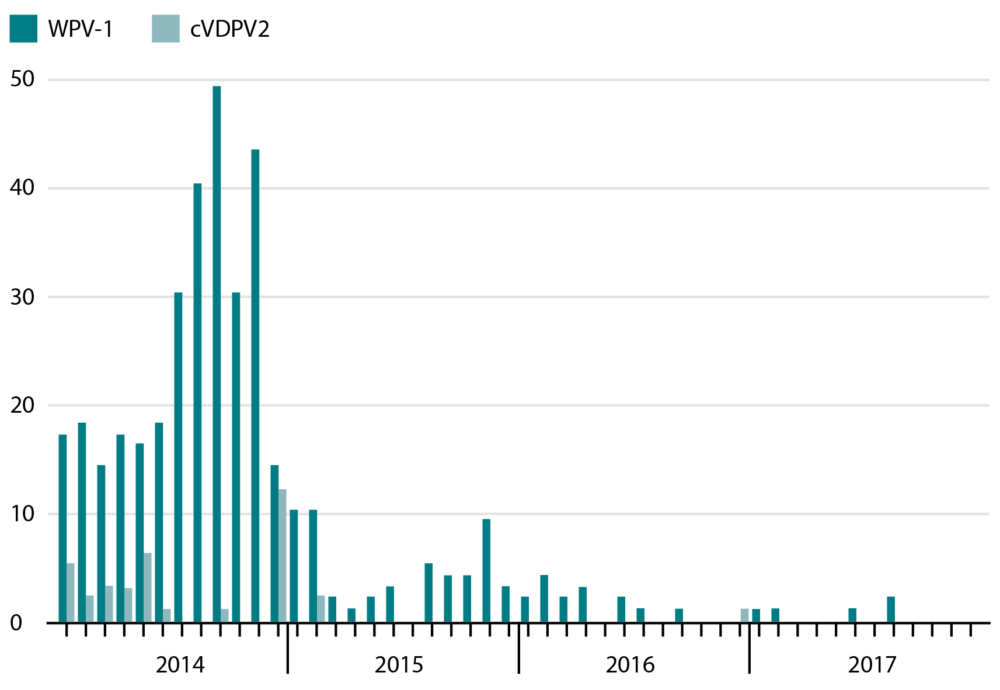

Back in Pakistan, 2014 was the worst year in its history for polio eradication – perhaps because vaccination workers were suspected of being foreign agents in disguise and so were attacked and killed in great numbers (see Figure 2).8

Figure 2: Number of cases of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV-1) and circulating vaccine derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) in Pakistan by month, 2014–2017.8

As a result, Pakistan became the centre of propagation of poliovirus. The ongoing wave of terrorism, followed by military action in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), led to the displacement of at least a million tribesmen, women and children. Anyone carrying the vaccine ran the risk of having their hand chopped off, and there are reports of people hiding the vaccine in a flask and administering it to their children. This raised questions about the cold chain maintenance and therefore the efficacy of the vaccine. Very few children of displaced families have received the vaccine and they now need to be specifically targeted.9

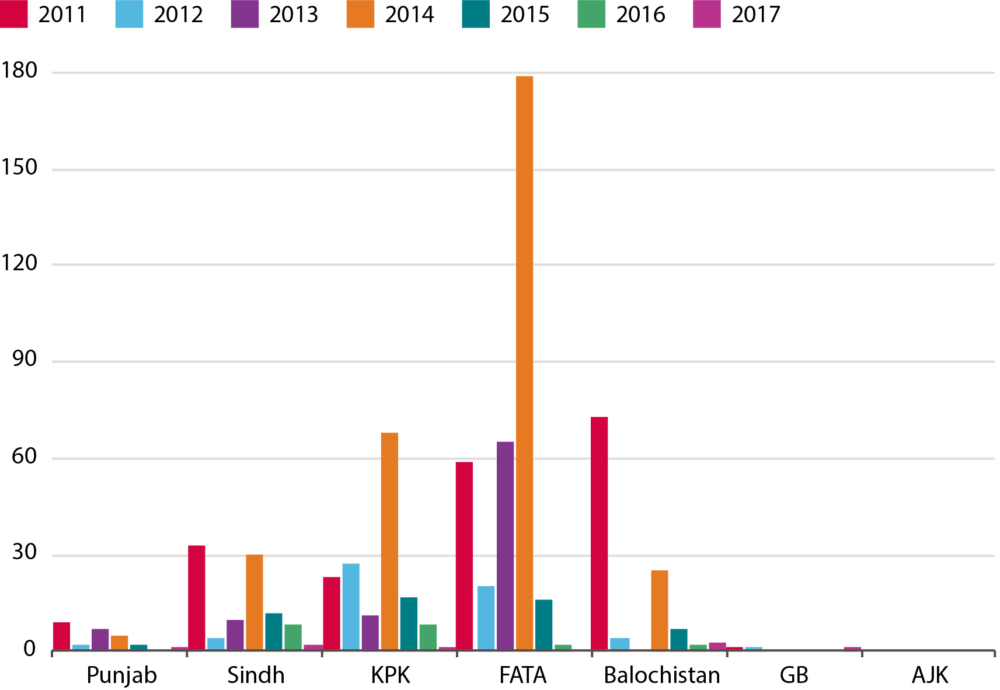

A case of paralytic polio is just the tip of the iceberg, as it may be accompanied by hundreds of asymptomatically infected people, who excrete the virus in their faeces. From the sewage, it makes its way back to the drinking water. In 2014, there was a five-fold increase in reporting of paralytic cases, affected by WPV-1, compared with 2013. 87% of cases were seen in the FATA and in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) (see Figure 3).10 The WPV trickled into major urban centres, where internally displaced people took refuge. In the sewage of metropolitan areas, WPV-1 – along with two strains of vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) – were discovered with increasing frequency. The affected cities had sporadic cases and there was no major outbreak, mainly due to herd immunity of the urban population.11,12

Figure 3: Number of annual cases of polio by province

KPK: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; FATA: Federally Administered Tribal Area; GB: Gilgit-Baltistan; AJK: Azad Jammu and Kashmir10

The impact of terrorism on the vaccination programme

As it was obvious that the main upsurge of polio cases was seen in the FATA – the main hub of terrorist camps and infrastructure – the Pakistan armed forces launched decisive action in June 2014 and the area was cleared of terrorists.13 This has obviously resulted in the control of polio, as the vaccine reached the area after restoration of law and order. Moreover, the internally displaced people had a chance to vaccinate their children, which had not been possible in the areas under militant control. There was, however, a backlash of military action in the FATA. In addition, some of the terrorists spread throughout the country and continued to target polio vaccine workers across Pakistan. A country-wide counterterrorism operation ‘Zarb-e-Azb’ has resulted in complete restoration of the rule of the state. Currently, no area in Pakistan is under militant occupation, with the exception of a few scattered pockets of influence and sleeper cells.14

The current situation: cause for hope

The situation improved with national commitment to intensive vaccination campaigns. Infrastructure was developed so that vaccinations would reach every household during consecutive vaccination campaigns. Still, there were a few gaps left. The concerted efforts and accessibility to high-risk districts have led to the decline of polio cases, but the WHO target will still be missed. By the end of 2017, the WPV, as well as VDPV strains, were still in circulation, in different parts of the country, despite the lowest number of polio-associated AFP cases recorded. The virus was isolated by cell culture from 18% of environmental samples. The samples were mainly taken from the KPK (40%), with 20% also from Balochistan and 14% from Sindh.

The environmental samples collected in the Punjab yielded no positive culture for polio, but Islamabad still had one. In 2018, a monthly vaccination programme was launched. In its first campaign, from 15 to 18 January, a maximum number of 39.4 million children were vaccinated by 260,000 workers (62% of them women). The areas bordering Afghanistan and the communities crossing the border frequently are the main target of the vaccination programme.15 Meanwhile, the situation has also improved in neighbouring Afghanistan, where 6 million children under five years of age were vaccinated on sub-national immunisation days across 187 districts in 24 provinces. There were permanent transit teams, which vaccinated 1.1 million children, and cross-border teams, which vaccinated 70,000 children.16

According to the WHO, there was one reported WPV-1 case by the end of May 2018, from the Dukki district in Balochistan. There were four new WPV-1 positive environmental samples reported by the end of May 2018, all collected on 10 May in Rawalpindi, Punjab (two samples); Karachi Gadap, Sindh; and Peshawar, KPK. During the second immunisation campaign, in May, teams worked to reach over 20 million children with the bivalent OPV. The vaccination campaigns in 2018 have had an extraordinary scale and reach – approximately 92.5% coverage. Approximately 1.5 million children were vaccinated at 386 permanent transit points in bus and railway stations and key road junctions.

In Afghanistan, a new case of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV-1) was reported during the last week of May. The patient, from Kandahar, experienced the onset of paralysis on 27 April. There were nine WPV-1 cases in 2018 in that area. Two new WPV-1 positive environmental samples were reported in May, from Jalalabad in Nangarhar, collected on 26 March and 24 April. During the May immunisation campaign, teams reached more than

9.6 million children with bivalent OPV.17

The most recent reported case in Pakistan was of an 18-month-old boy, who experienced the onset of paralysis on 18 May, and the virus was confirmed after his death. The child had missed OPV drops in the routine programme, and had only received three doses across all campaigns (and only one dose in the last six campaigns). Afghanistan has reported nine cases of polio this year. The total number of cases in the world now stands at 12. In Pakistan, more than 25 environmental samples have tested positive, indicating that the virus was still circulating in Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Jacobabad, Lahore, Multan, Peshawar, Bannu, D.I. Khan, Quetta, Killa Abdullah, Chaman, Loralai, and Dukki.18

At the moment, in Pakistan, AFP and environmental surveillance is being regularly conducted but transmission of the polio virus is ongoing. The type 2 component of OPV has been completely withdrawn and a bivalent OPV vaccine (serotype 1 and 3) is now in use. The IPV has been included in routine immunisation, but the OPV has not been withdrawn yet.19

A national emergency action plan to eradicate polio in Pakistan has been launched to reach all children by routine vaccination through at least five vaccination days over the year. Efforts will be concentrated on high-risk districts, surveillance of cases of AFP, reaching missed children, audits and vaccination at transit points. As a result, public confidence has improved and efforts have intensified. As the IPV replaces the OPV, it is expected that the circulation of vaccine-derived strains will end. Meanwhile, environmental sampling will continue. A polio reference lab has been established in the National Institute of Health in Islamabad. The travel requirements laid down by the WHO will continue for the time being (i.e. a vaccination certificate is required to obtain a visa to travel to any country with an embassy in Pakistan, and all visitors who have stayed in Pakistan for more than one month are vaccinated on leaving the country). Pakistan has missed the chance of being polio free for now, but it is hoped that the dream will come true in the near future.20 There is a need for continued national commitment and optimum utilisation of resources to achieve this goal.

References for this article are available on our references pages.